From the series “What is the role of a fund manager? Who needs a fund manager? Index funds and the ABC of long-term investing“

Ever heard of Efficient market hypothesis? Don’t worry, it is nothing unfathomable.

The price of securities is affected by a number of different factors, e.g. corporate results, economic growth expectations, etc.

Present-day financial thinking is built upon the idea that the market price of securities should always reflect the relevant information. Therefore, no investor is able to consistently earn higher-than-market-average yield over a long period of time. This is what is referred to as the Efficient Market Hypothesis.

We have all heard stories of exceptionally successful investors. For example, Warren Buffett, who started out with USD 170,000 and used securities investments to build up a net worth of USD 65 billion over a period of 60 years. That is a reality. Or at least an exceptional example of reality.

So what is going on? Indeed, the contradiction between theory and exceptions evident in practice is the reason why the money world is full of myths and heated debates. Analysis centres have gathered a lot of evidence suggesting that the markets are not actually efficient. The more contemporary, behaviouristic path tries to take into account the fact that investors are human beings, rather than calculating robots programmed to maximise profit. Indeed, bubbles and panics on the market are created by human emotion.

An experienced financial shark should be able to foresee the dynamics. An educated push on the right pedal – the accelerator or the brake – could allow him to post results that surpass the market average. The banks operating in Estonia are also trying to convince you that they have recruited expert fund managers who are able to ensure a higher-than-market-average yield.

Everyone is trying to outsmart the market but most of us fail. Some of us might pull it off over a short term, but only a handful will be successful in these efforts over a longer period of time. Yet hope remains. To convince themselves and potential customers, experts have resorted to introducing increasingly complicated terms and progressively fantastic calculations.

Unless mathematics is a passion of yours, the hodgepodge of figures and monetary jargon is bound to confuse. Nonetheless, if we concentrate on the basic principles, things will start to make more sense.

Just consider this – who is this miraculous person that is supposed to ensure a yield higher than the market?

Option one: what if Buffett is just lucky?

Let us consider the factors allowing some investors to beat the market? For this purpose, let us return to Warren Buffett. Quite clearly, Buffett has been an exceptionally successful investor. Why?

Option one: he just happens to be lucky. Unbelievable, is it not? Indeed, it is highly unlikely – even though possible in principle – for someone to be as lucky as Buffett by chance.

On the other hand, it is quite possible, even quite certain, for an investor to post a higher-than-market-average yield over a certain period of time by chance.

It is also quite certain that those, who do well for a while, will consider themselves experts and will start seeking wider-ranging explanations for their success. There are a number of books available on Amazon by lucky lottery winners who are now teaching others “fool proof” strategies of how to win the lottery. Even more investment books have been written by those who have been lucky on the securities market…

Warren Buffett himself once pointed out an amusing example of how a coin-flipping contest quickly produces “experts” – people whose coin accidentally fell the right side up for a number of times in a row, and who thus became millionaires. Such lucky winners are soon to lose, Buffett predicted. “They will probably write books on “How I turned a Dollar into a Million in Twenty Days Working Thirty Seconds a Morning.” Sound familiar?

Option two: Buffett is smarter than others

Is Buffett able to foresee things others cannot?

Warren Buffett and several other world-famous super-investors have one thing in common – they all studied value-based investment logic in Columbia University under the supervision of professors Benjamin Graham and David Dodd. Graham and Dodd taught their students to look for any dissonance between the market price of shares and the actual value of the business. The same principles are taught by professors in hundreds of business schools all over the world. Perhaps Graham and Dodd were the best teachers. Perhaps Buffet was an exceptionally talented student.

Option three: inside information

How exactly is Buffett able to identify these dissonances between the market price and corporate value, missed by all other investors? Could this be attributed to inside information that others have no access to? This, too, is possible. In today’s world, Buffett is a very powerful individual and is often visited by important persons with important agendas.

Even though the use of inside information is strictly regulated on the securities markets, powerful investors inevitably have access to CEOs of publicly traded global companies, owners of major family businesses, analysis teams of leading investment banks and other information carriers. It confers an advantage.

How do we measure a fund manager?

In all likelihood, Buffett is able to benefit from all three factors: luck, meaningful analysis and better access to information. Indeed, we are dealing with a highly exceptional investor. Nonetheless, I would not dare to predict the future for anyone, even for Buffett.

But how do we determine whether our fund manager is exceptional?

Even though past events are no predictors of the future, it would nonetheless be wise to look at previous performance. If the funds managed by the fund manager have failed to beat the market, there is no real reason to hope that the fund manager has concealed his talent and will do better in the future. No pension fund manager currently operating in Estonia has succeeded in beating the market over a long period of time.

Still, if you succeed in finding someone who has beaten the market average, remind yourself of the above three success factors: luck, the ability to predict market behaviour and above-par access to information.

Look the person in the eye and ask a few questions. Would it be fair to say that their skills of market analysis significantly exceed those of their peers? Do they regularly have lunch with mighty figures of the international financial world? Or have they just been lucky?

Probably the latter. If you are in to it, you can consult an astrologist to find out whether they are likely to be successful in the future. Jokes aside, in your search for answers, you should remember two things.

Firstly, you are not only looking for someone practical. You are looking for someone exceptional. Global experience has shown that an average fund manager is unable to beat the market. It is extremely difficult to find a person who can single-handedly outsmart the “collective wisdom” of millions of people over a longer period of time.

Secondly, I bet your fund manager considers themselves better than average both when they excel and when they totally suck.

Do you remember the famous test conducted in the 1980s, with psychologist Ola Svenson asking 161 students to give themselves a rating according to whether they consider themselves to be better than average or worse than average drivers. In a random sample, approximately half of the people should be better than average and the remaining half worse than average, should they not? Nonetheless, a majority of those polled considered themselves better than average.

So here we are. Your fund manager’s self-esteem depends on whether or not they can find ways to convince themselves that they are better than average – even if experience shows that the opposite is true. Their income depends on whether or not they will be able to convince you that they are better than average. Your income depends on whether or not you can realistically assess their abilities.

If you do not consider yourself an expert, you should place your trust in probability: a majority of fund managers never beat the market and, in all likelihood, your fund manager is among them. (Side note: the fact that you do not consider yourself an expert is a good sign: at least overconfidence will not jeopardise your chances of earning a reasonable long-term yield.)

To sum up, only a very few people are able to beat the market average over a long period of time. Since no-one really knows why these few are so successful, past success is no guarantee of the future. Indeed, this might be the reason why Warren Buffett advised his heirs to iinvest pension assets in low-cost index funds.

I, along with other founders of Tuleva, believe that a person who makes regular investments in small amounts will profit the most from an index fund. The second-pillar pension saver is exactly this type of investor. But what is an index fund?

What is an index fund?

A securities index is simply an imaginary securities portfolio, i.e. a list containing the names and proportions of securities. There is a number of such lists – the best-known index compilers include S&P, MSCI and the Financial Times.

An index fund is a fund that automatically follows one or several indices. In other words – an index fund buys and holds the securities included in the index list in the exact proportion specified in the list.

A majority of modern-day indices simply base the proportion of securities on their market value. For instance, Apple’s proportion of the world’s most broad-based stock market index (MSCI ACWI) is 1.5%. This means that 1.5% of the funds transferred to an index fund governed by that particular index will automatically be invested in Apple stocks.

In other words, your money will be divided between securities proportionally with market segmentation. If you believe that markets are efficient, good for you: you will benefit from the market’s collective decisions without much effort, regardless of what influenced these decisions. If you do not believe that markets are entirely efficient, the index will still be a simple and cheap method of dispersing the securities portfolio.

“Low cost” is the keyword. We should remind ourselves that “cheaper” and “better” are almost synonyms in the investment dictionary. The higher the operating expenses of the investment fund management company, the greater the proportion of yield swallowed up by commission fees. Some management companies are trying to convince you of the opposite, comparing high-end stores with discount stores, or iPhones with Nokia bricks. I would advise treating such comparisons as a warning of the (un)reliability of the person.

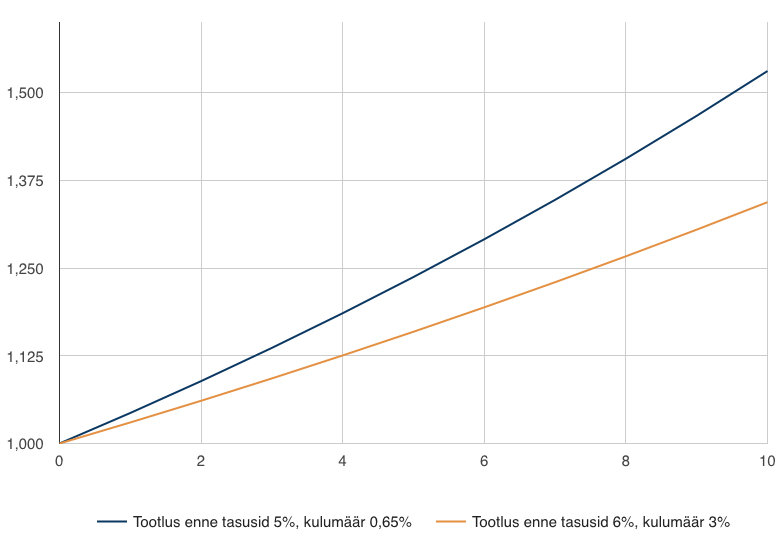

The yield of an index fund is never exactly on par with the average market yield. Where the total expense ratio of the fund is, for example, 0.65%, the yield of the index fund is always 0.65% lower than the index yield.

For example, if the market grows an annual 5%, then the EUR 1,000 initially invested will, in ten years, grow by 5% – 0.65% = 4.35% annually. By the end of the tenth year, you will have a total of EUR 1,531.

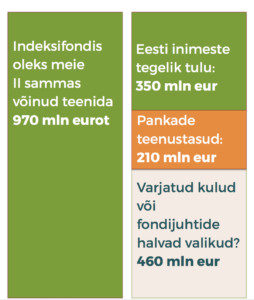

Let us now assume that the EUR 1,000 was invested in an actively managed fund, whose manager made the right calls and beat the market – e.g. achieving an annual 6% yield before commission fees. If the total expense ratio of the fund is an annual 3%, your actual annual yield will be 6% – 3% = 3%.. (Betterfinance.eu believes this to be the average for present-day Estonian pension funds.) By the end of the tenth year, you will thus have a total of EUR 1,344.

An actively managed fund may, of course, do even better. But it may also do worse. So far, Estonian fund managers have done worse.

An index fund will always give you a near-market-average yield. Nothing better but also nothing worse. No one can possibly predict what the yield will be over your lifespan. But when you read the newspaper, 20 years from now, and discover that the global securities markets have generated an average annual yield of X percent over the last two decades, you can be quite sure that the annual yield of your pension account will not differ much.

The cost rate of the world’s cheapest index funds is 0.1% or less. Tuleva aims at seeking opportunities for making these funds available to our members. The current obstacle is the small size of our market, but mainly the restrictions established by law. Against the backdrop of technological development, the size of the market is less and less important. Laws can be changed in the interests of pension savers. The more members we have, the stronger our resolve to serve as a partner to the government.

In the next chapter, I will discuss the motivation of fund managers. If you are already a member of Tuleva, feel free to comment and ask for additional information in our Facebook group or send me an e-mail.

It only takes a few minutes to transfer your pension to Tuleva. You do not have to be a member of Tuleva to transfer your pension, and changing funds doesn’t cost anything, you will be saving money on management fees instead! We have prepared a guide to help you out here: